In the bustling halls of Gamescom LATAM 2026, CD Projekt Red's associate game director, Pawel Sasko, pulled back the curtain on the intricate, often grueling, process of crafting the quests that define legendary games like The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt and Cyberpunk 2077. For Sasko, a quest is more than a task; it is an emotional conduit, a carefully engineered experience designed to bypass logic and speak directly to a player's empathy. The studio's renowned narrative pipeline, a journey from outline to polished release, is governed by a set of core commandments that prioritize player agency, dramatic gameplay, and profound consequence. This philosophy transforms digital worlds into spaces of authentic human experience, where every design decision, from a character's subtle leg shake to the fate of nations, is intentional.

The Blueprint: Quest Design Documents

At the heart of every CD Projekt Red quest lies its design document, a hybrid blueprint that is half technical design and half cinematic storyboard. These documents are living entities, evolving from game to game. "We've been working on a formula for many, many years, reinventing it for every game," Sasko explained. Their length varies dramatically: a minor side quest might be a single page, while an epic like The Witcher 3's "Bloody Baron" storyline ballooned to nearly 60 pages.

The cardinal rule? Describe exactly what happens on the screen, not the designer's intention. "It's meant to be that you're describing exactly what happens because that forces you, as a designer, to see the perspective of the player," Sasko emphasized. This player-centric focus is paramount. If a character like Jackie Welles is meant to feign confidence, the document wouldn't just state that; it would detail his entrance, his seated posture, and the anxious tremor in his leg. This granularity ensures the intended emotion reaches the player.

References are another crucial pillar. When designing Cyberpunk 2077's controversial "Sinnerman" quest, which involves a man seeking crucifixion via braindance, the team embedded deep cultural touchstones. Sasko directly referenced Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper to structure a pivotal scene. "If our players don't get it, it's fine... But when they get it, they feel clever," he said, highlighting how layered references reward engaged players without alienating others.

The Guiding Frame: Genre and Theme as Creative Boundaries

One of Sasko's key commandments is to define genre and theme early. He has witnessed the chaos of undefined direction. "When you have 400 [creative people], all of them are incredibly varied... we are a ship that is sailing somewhere. We cannot change the direction of the ship because we'd end up going in circles."

Paradoxically, he argues that strict boundaries fuel creativity. Giving a creative team a frame like "individuality versus authority"—the core theme of Phantom Liberty—provides inspirational focus. "It just inspires you so much because you learn the rules you can bend and you try to figure things out in new ways," Sasko stated, drawing a parallel to indie games like Animal Well, where severe technical limitations breed incredible innovation.

This thematic consistency ensures that hundreds of developers, working on disparate content, are all whispering variations of the same story. It prevents a tonal "goulash" and protects the immersive atmosphere critical to games like The Witcher and Cyberpunk. Every small decision—a piece of music, an environmental detail—contributes to this unified whole.

The Golden Rule: Play, Show, Tell

Perhaps the most foundational principle Sasko shared is the sacred order of engagement: Play, Show, and Tell, only in this order.

-

Play First: "It's our medium. It's an interactive one," Sasko asserted, distancing CDPR's work from cinematic, non-interactive games. The core experience is built through player action—making choices, building a character, carving a unique path. Drama should be built through gameplay whenever possible. He contrasted a well-written scene with the visceral terror of being hunted by the Cerberus robot in Phantom Liberty's "Somewhat Damaged" quest. "It's just on such a different level." Play creates memorable, fun, and deeply personal experiences.

-

Show Second: When you see rather than are told, reality and immersion deepen. Sasko pointed to Cyberpunk's "Briefing" sequences, where plans are visualized on a holographic shard, transforming a simple exposition dump into a moment that makes the player feel like part of a heist crew. Showing also taps directly into human empathy. "If you tell someone that something's sad, it's one thing, but when you see them sad... it's another thing." He recalled the profound emotional impact of the Bloody Baron carrying his botchling child, a moment that resonated powerfully with players who had experienced personal loss. "That's what I mean about touching people on an empathic level."

-

Tell Last: Telling is the fallback option, used when budget, time, or pacing demands it. The key is to use "tell" cleverly to avoid repetition and boredom. A favorite trick in Cyberpunk and Phantom Liberty is having an NPC pre-empt the player's report by saying, "Oh yeah, I know. I already talked to them," seamlessly advancing the narrative without redundant dialogue.

The Crucible: Designing the Most Difficult Quests

Sasko has been in the trenches on some of gaming's most complex narrative sequences. He described The Witcher 3's "Battle of Kaer Morhen" as a monumental challenge due to its sheer combinatorial complexity. With up to 16 possible characters participating, each requiring meaningful, unique moments, the branching design was a nightmare. Furthermore, he faced the unique design puzzle of making the player feel like they were losing a desperate defensive battle while the gameplay allowed them to win. His solution was Yennefer's shrinking protective spell, a visual metaphor for the relentless pressure of the Wild Hunt.

For Cyberpunk 2077, the hardest task was the Kerry Eurodyne concert quest, "A Like Supreme." The technical hurdles were immense: syncing mocapped band member animations perfectly to the music's beat, managing memory to fill the club with a lively crowd, and allowing player interaction during the performance. "They cannot be offbeat," Sasko stressed, highlighting the new audio-animation syncing technology required.

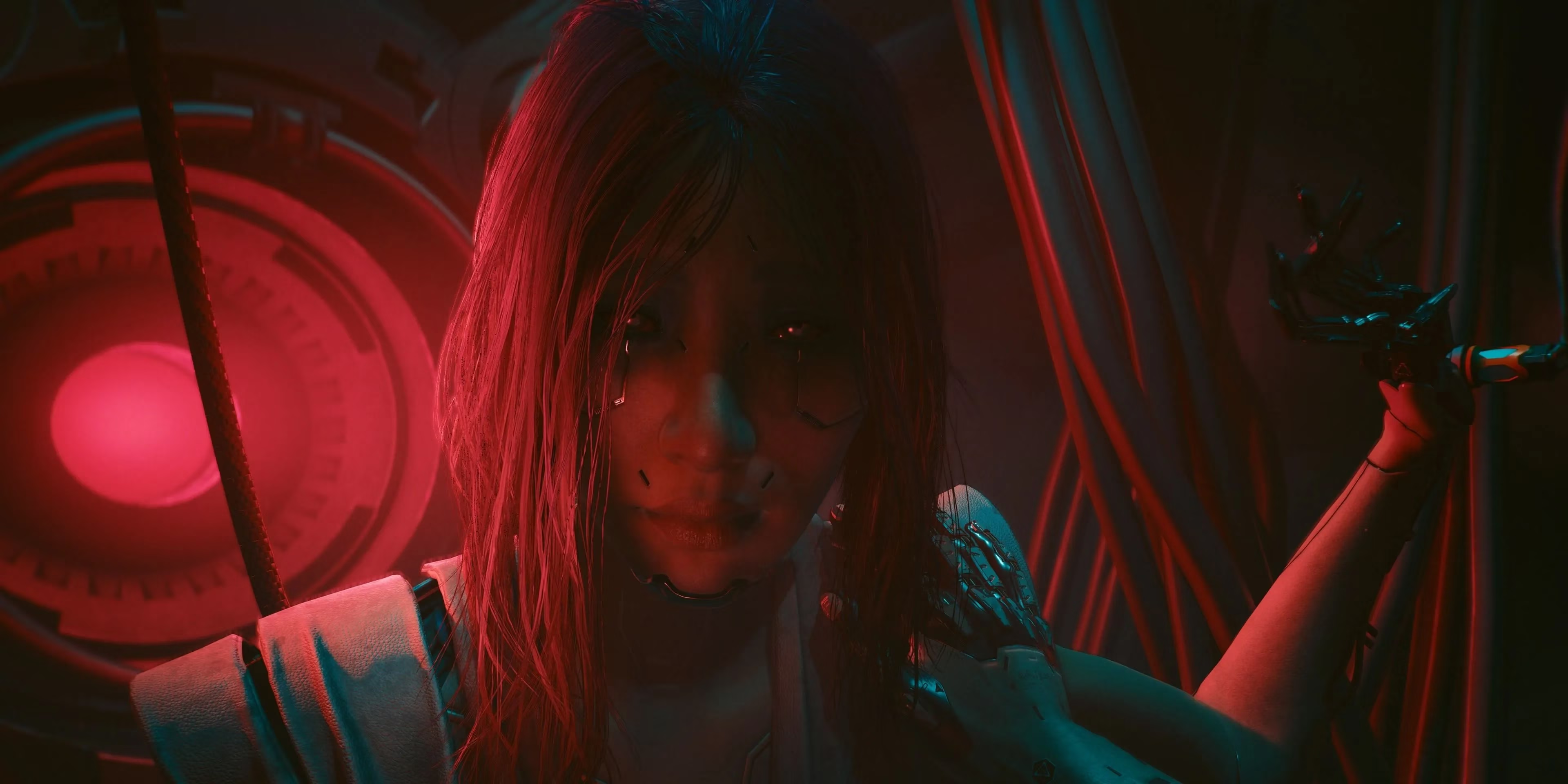

In Phantom Liberty, the crown for difficulty goes to the horror quest "Somewhat Damaged." The challenge was twofold: ensuring the entire team understood they were building a taut, terrifying "minotaur in a labyrinth" experience, and technically realizing the fully AI-driven Cerberus enemy that could climb vents, react to sound, and stalk the player unpredictably in a complex environment.

The Weight of Choice: Asymmetrical Consequences

A key tenet of CDPR's design is that consequences must be asymmetrical. "Otherwise it kind of feels like the same game," Sasko noted. The goal is to make each player's path feel uniquely theirs. The process starts not with balancing branches but with authenticity. Designers ask, "What is authentic, what is natural, and what would feel good to your empathy?"

He cited Phantom Liberty's "Balls to the Walls" quest, where characters Paco and Babs can either die or survive. In the survival branch, they later message the player from Nairobi, sending a Cyberpunk-ified photo of the city's iconic building. This follow-up exists only on that branch, enriching it without forcing an equivalent reward on the other. "We're always saying to ourselves that, no, you can absolutely and completely do it asymmetrical, do much more on one branch than another," Sasko affirmed. This creates a tapestry where one player's short branch in a quest is balanced by a long branch in another, based entirely on their choices, reinforcing the feeling of a personal story.

A Glimpse into the Future and a Thriving Market

Reflecting on Gamescom LATAM itself, Sasko was impressed by the event's scale and the vibrant creativity of the local scene. "There are just numerous indie games being made in Brazil... whose games had roots in Brazilian culture," he observed, seeing it as a sign of the market's growing global importance. The professionalism, the passionate players with multiple consoles, and the presence of major international brands all signaled a thriving community. And, with a laugh, he added one final, crucial assessment: "Also, the food here is f*cking great."

Through Sasko's insights, it becomes clear that for CD Projekt Red, quest design is a discipline of profound empathy and meticulous craft. It is about building boundaries to unleash creativity, prioritizing interactive drama over passive spectacle, and weaving choices with consequences that feel authentically human. It is a process that demands designers see through the player's eyes, feel with the player's heart, and ultimately, tell stories that linger long after the controller is set down.